Are emerging environmental contaminants a threat to male fertility?

Unexplained male infertility is evident in up to 25% of male factor infertility cases and exposure to environmental contaminants could be one of many culprits in the global decline in male fertility. Since many of these compounds end up in water bodies, it is referred to as Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) and are typically not regulated under current environmental laws.

Origin and health impact of CECs

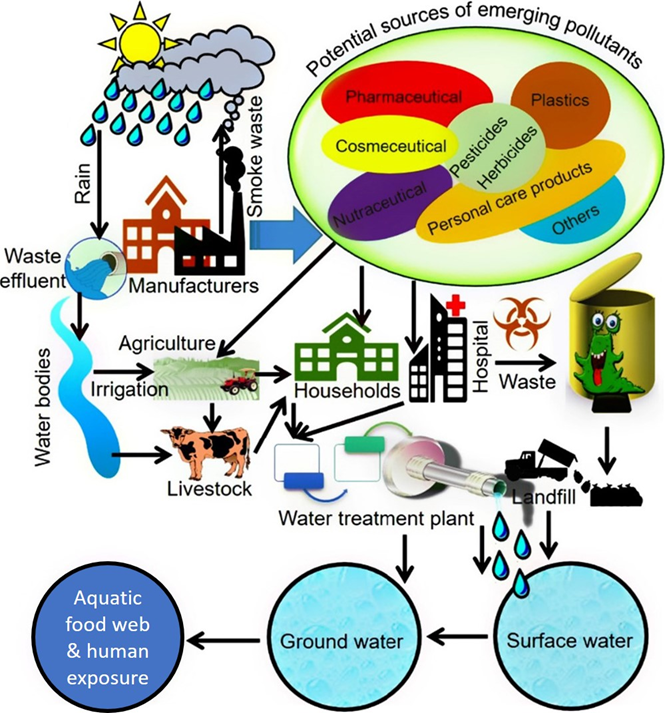

One of the main consequences of industrialization is the production, use and discharge of several CECs, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products and pesticides. The presence of CECs is well-documented in a wide range of environmental and food matrices, such as surface water, wastewater, soil, livestock manure, human waste, plants and seafood (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Major sources of emerging contaminants and its distribution to water bodies (adapted from Rasheed et al. 2019).

The large-scale use of CECs has resulted in their ubiquitous occurrence in surface and ground water sources and has caused great concern among the scientific community and regulatory authorities in recent years. In addition, current water treatment techniques (e.g. biodegradation, flocculation, ozonation, electrodialysis, reverse osmosis and sedimentation) are not sufficient enough or unable to completely degrade many CECs. As a result, human populations can be exposed to CECs by drinking contaminated water, consuming aquatic species affected by CECs or even recreational activities in affected water bodies.

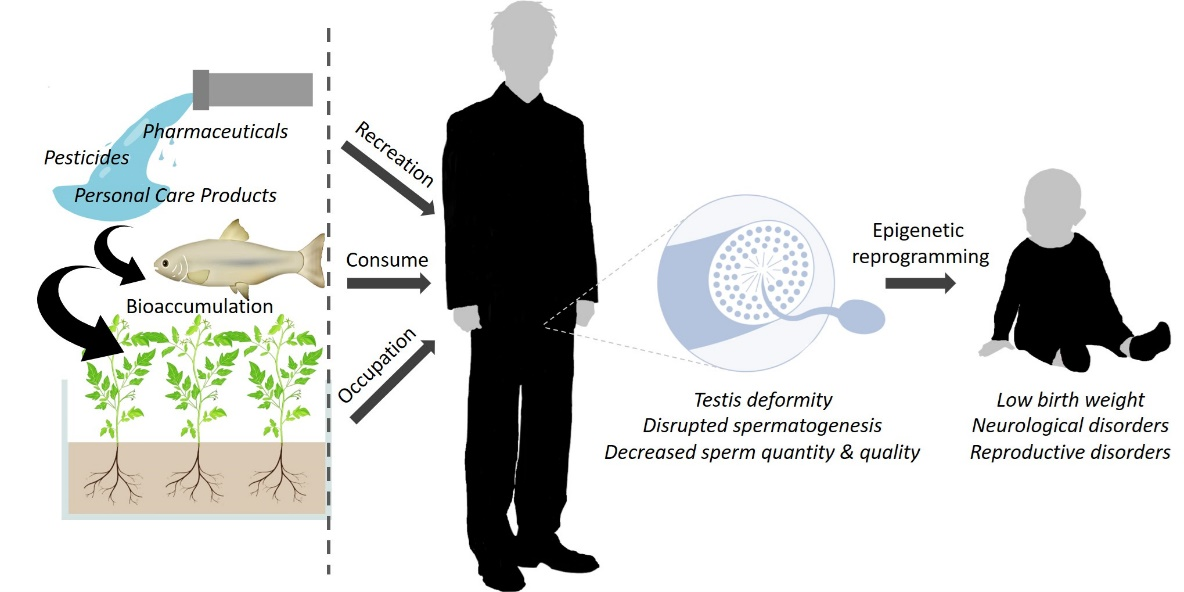

CECs generally refer to compounds that have not previously been detected or only detected in small quantities through water quality analysis and thus the risk they pose to human or environmental health is not yet fully understood. While researchers have started to examine the adverse effects of CEC exposures on human health, including fertility, it has provided varied findings. Many CECs mimic the action of hormones in the body and can disrupt the endocrine system and subsequent basic physiological functions, while others are classified as carcinogens. The prevalent male reproductive side effects of exposure to CECs include gonadal malformations, interference with spermatogenesis, hormone imbalances, and demasculinisation, as was shown for a variety of vertebrates including fish, turtles, birds and mice. In addition, it is suggested that CECs may have a harmful effect on the offspring of affected parents via the inheritance of epigenetic markers. Therefore, parental exposure to the CECs will not only affect the parents themselves but also leave profound signatures in the germline, compromising the health of the next generations (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Effects of contaminants of emerging concern from the source to the offspring of exposed individuals.

Recent reports on CECs in the marine environment

The Environmental and Nano Science Research Group (Department of Chemistry, University of the Western Cape, South Africa) under the leadership of Prof Leslie Petrik has investigated the occurrence and accumulation of various CECs (including herbicides, pharmaceutical and personal care products) in the marine environment around Cape Town. Many of the CECs detected are most likely due to several wastewater-treatment plants discharging improperly treated effluents into the ocean. Prof Petrik and co-workers reported that the levels of CECs in the seawater, sediment and several marine organisms (seaweed, invertebrates and fish) pose a low acute and chronic risk to various tropic levels due to its bioaccumulation factor and calculated risk quotients.

Current investigation on the effect of CECs on sperm function

Figure 3: CEC team in the Comparative Spermatology Group: Daniel Marcu, Shannen Keyser, Liana Maree and Monique Bennett.

The Comparative Spermatology Group (Department of Medical Bioscience, University of the Western Cape, South Africa) has joined forces with the Environmental and Nano Science Research Group in deciphering the potential consequence or mechanisms of action of CEC exposure on sperm function in vitro. Two PhD students, Daniel Marcu (School of Biological Science, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom) and Shannen Keyser (Comparative Spermatology Laboratory) (Figure 3), have studied the effects of the most prevalent CECs found in our marine sources on human sperm function, including anti-inflammatory and antibiotic drugs, as well as some herbicides, using computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA).

One of the advantages of CASA is that it allows the researcher to visualize, evaluate and obtain precise information on the swimming characteristics of individual sperm. CASA applications are limitless, and they provide instrumental insights in reproductive toxicology and human fertility. Understanding the specific kinematics and the molecular events underpinning them is of great importance for establishing toxicology level cut-offs for sperm function.

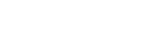

Our preliminary results after sperm from donor samples were chronically exposed to several contaminants indicate that the various chemicals disrupt the sperm plasma membrane and metabolic processes. While exposure to the CECs typically decreased the percentage total and progressive motility (Figure 4), more significant adverse effects were found on the kinematic parameters (such as VAP, VSL and BCF), especially in that of the slow and medium progressive speed groups. It was further noted that some of the CECs has varying effects on different motility sperm subpopulations. We are in the process of also assessing its effect of other sperm functional parameters, e.g. vitality, hyperactivation and acrosome reaction.

Figure 4: Motility parameters of a high motile sperm subpopulation of after 30 minutes exposure to various concentrations of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory Naproxen.

Note: 1 mg/mL Naproxen significantly decreased the percentage progressive motility and MP progressive speed groups as compared to the control and other concentrations. Abbreviations: MP, medium progressive; NP, non-progressive; Prog, progressive and RP, rapid progressive.

Apart from using human sperm to investigate the effect of CECs on sperm function, we also embarked on studying its effect on sperm from broad cast spawners, such as sea urchin and oyster. These species are presumably directly affected by the exposure to contaminants in their marine environment and are known to bioaccumulate CECs. Such testing could in future act as a warning system that identifies the causes of population decline in animal populations, offering potential interventions for conservation of entire ecosystems. Through our investigations, we also hope to increase public awareness about the threat of CEC exposure to the environment and human health.

Dr Liana Maree (PhD)

Comparative Spermatology Laboratory

Department of Medical Bioscience, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

Daniel Marcu (PhD Candidate)

School of Biological Science, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom

Daniel has joined the Comparative Spermatology Lab to fulfil a three-month internship via the Norwich Biosciences Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP)

Shannen Keyser (PhD Candidate)

Comparative Spermatology Laboratory

Department of Medical Bioscience, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

Leave A Comment