The evolutionary consequences of sperm competition or the lack of sperm competition

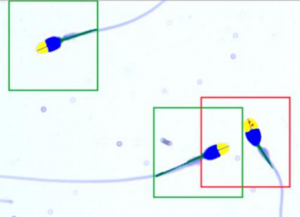

Fig. 1: Scanning EM: Gerbil sperm.

What is sperm competition? It is the competitive process between spermatozoa of two or more different males to fertilize the same egg(s) during sexual reproduction. This form of competitive reproduction is by far the most common one in the animal Kingdom. What about the lack of sperm competition? The most extreme form of the absence of sperm competition represents a female that will only mate with one male for a lifetime.

In this blog I will discuss examples of these extremes as well as other reproductive strategies. The main question to be addressed is what are the evolutionary consequences of sperm competition in terms of sperm form and function.

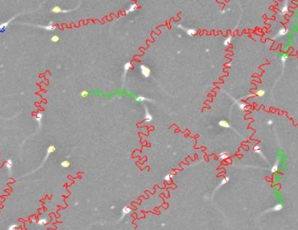

Fig. 2: Bottlenose dolphin sperm analysed by means of SCA Evolution CASA, Sperm in green blocks normal with acrosome yellow, rest of head blue and green midpiece. Red dots show fragmentation.

While sperm competition occurs in all animal phyla I will concentrate mainly on mammals. Often sperm structure in a species with a high level/high risk of sperm completion as in many rodents is very elaborate and most sperm are almost perfectly shaped. Many examples will suffice but in Fig. 1 sperm of a gerbil species provides an excellent example showing a distinct elongated acrosome and an extensive midpiece with dozens of tightly packed mitochondria in helical form. More than 90% morphologically normal sperm with very similar morphometric features are evident in Bottlenose dolphin (Fig. 2). In this species as many as eight males copulate with a single female within minutes rather than hours and represents an extreme risk in sperm competition. Furthermore, species such as the above has a very high sperm concentration, a high percentage of motile sperm and a high percentage of rapid swimming sperm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Highly motile and rapid swimming typical where there is a high level of sperm competition. Red tracks represent rapid sperm.

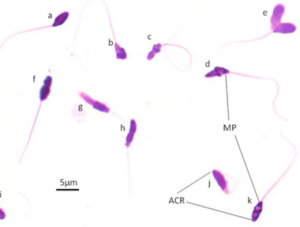

In contrast species with a low risk of sperm competition typically has morphologically polymorphic (many different morphological forms) sperm and many of these are abnormal. The naked mole rat represents an extreme in this instance with only about 5% morphologically normal sperm and most sperm are vastly abnormal and the sperm design reflects simplicity and “degeneration” (Fig. 4). In this species the female selects one male for life and there is accordingly a low risk of sperm competition. In addition, only about 15% of the sperm in the ejaculate is motile and these sperm are slow swimming with their short tails.

What about Primates including humans? Chimpanzees are not only very promiscuous but simply by a study of their high quality sperm traits show a high risk of sperm competition. In contrast gorillas and humans are more closely aligned to monogamous groups typically forming pairs. Evolutionary history indicates that at least during the last 25 000 years’ humans have been mainly monogamous. It seems that living in small family groups this strategy may provide a better chance for the care and protection of offspring.

Fig.4: Polymorphic and highly abnormal sperm of the naked mole rat (lack of sperm Competition) (Modified after vd H, Maree).

But the question arises now why would there be selection for poor sperm quality in species with a low risk of sperm competition? It seems evident that if an individual has just enough sperm of a reasonable quality to fertilize oocytes and leave viable offspring there does not seem to be a need to invest energy in producing a “Roll Royce” sperm. In contrast with a high level of sperm competition almost every sperm needs to be perfect. The author believes that the typical low WHO cut-off points for human semen quality further supports the idea that humans had a long evolutionary history of monogamy and accordingly there has been a low selective pressure to produce better sperm. In contrast species with a very high level of species competition has the advantage that even if the best sperm does not fertilize the oocytes the second best will still be of potentially very high quality. But then the production of such super high quality sperm comes at an energy cost.

Fig. 5: Transmission electron micrograph of naked mole rat sperm showing large light areas in nucleus representing fragmentation (Modified from Van der Horst and Maree).

An aspect of potential concern, particularly in the naked mole rat is that virtually all sperm show signs of fragmentation (Fig.5) (even in humans this can be as high as 50%) and it is well known that these sperm can either not fertilize the oocyte or later on cause major developmental problems in the embryo. But then the oocyte comes to the rescue as young well-formed mature oocytes can repair DNA damage both of the single or double stranded type in sperm. A further complication in humans appear to be the decline in oocyte quality to repair sperm DNA. Age of the female is a factor as repairing faulty DNA becomes seriously impaired from the age of about 38.

In conclusion it appears that evolutionary forces play an important role to “shape” sperm quality of a species also among others on the basis of sperm competition and what is ultimately required to fertilize the oocyte. Apparently, the main evolutionary consequence is that no energy must be wasted if not absolutely required!

Prof Gerhard van der Horst (PhD, PhD)

Senior Consultant

MICROPTIC S.L.

Leave A Comment